Author’s Column by Tymur Levitin — Language, Meaning & Cultural Reality

“A teacher doesn’t always say what’s nice — he says what’s necessary.”

🔹 Introduction

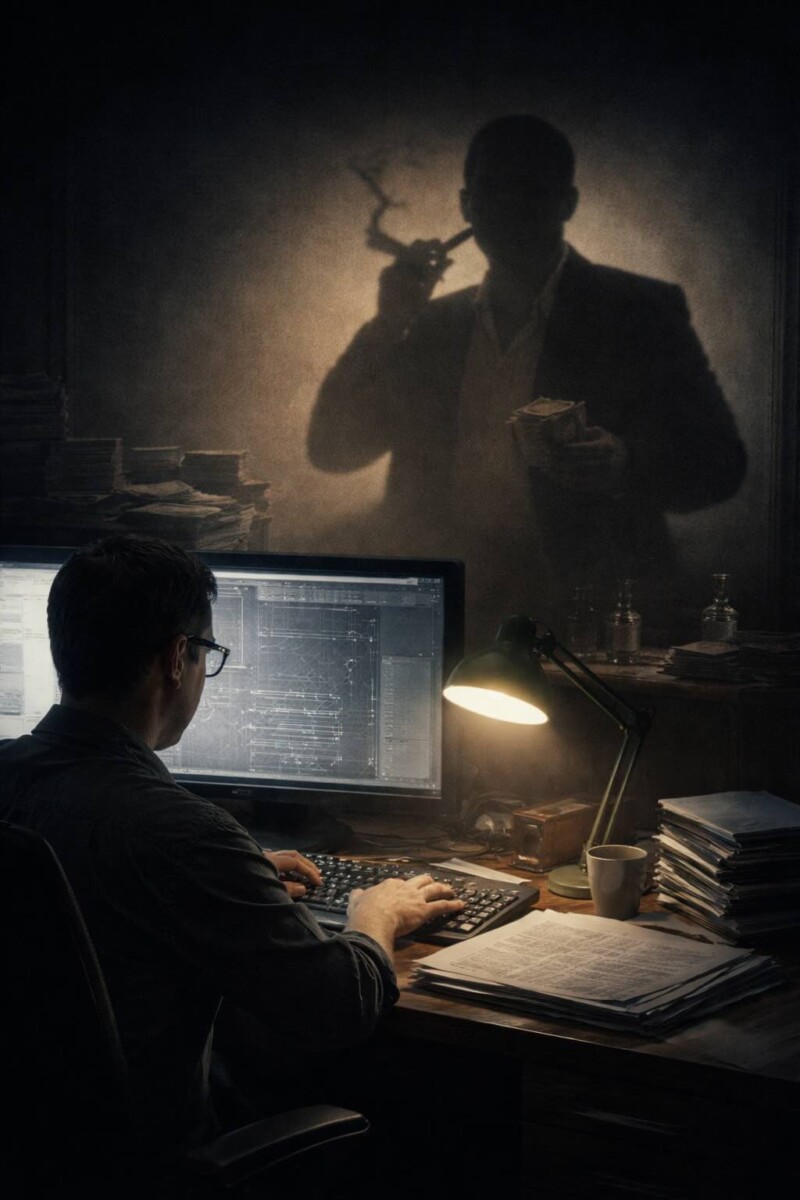

Once upon a time, a backroom boy was a figure of respect. He was the genius in the shadows — a quiet mind behind great inventions, the strategist no one saw, the architect behind the curtain. He wasn’t in the spotlight, but he made things work. That’s how we were taught — not just in linguistics, but in life.

And yet, if you say “backroom boy” today, you might get a smirk. If you talk about “backroom deals” or “backdoor access,” the associations quickly shift — not to intellect or strategy, but to secrecy, corruption, and often… sex.

So what happened?

How did a neutral or even noble phrase become a red-flag expression?

And more importantly:

Why does it matter for students — and teachers — to understand this?

🔹 Back Then: Genius in the Shadows

In British English of the mid-20th century, “backroom boy” referred to the engineers, scientists, and planners who worked behind the scenes — especially in wartime. These were not public heroes, but real ones. The phrase carried respect, even reverence.

Think of Alan Turing, Bletchley Park, or the early computer pioneers.

These were the backroom boys.

In classroom pragmatics, we often cited this term as an example of neutral-positive occupational lexicon. It had no dirty connotation. It was a phrase of quiet brilliance.

🔹 What Changed: From Strategy to Sleaze

But language doesn’t live in textbooks. It lives in culture.

As media evolved — from spy thrillers to political dramas to tabloid gossip — the word “backroom” began to mutate:

| Term | Early Meaning | Current Meaning / Use |

|---|---|---|

| Backroom boy | Technical genius | Rare, often misunderstood |

| Backroom deal | Confidential negotiation | Corruption, manipulation |

| Backroom | Private work space | Secret sex room / hidden agendas |

| Backdoor | Alternative entrance (literal) | Hacking / anal sex / shady access |

Today, especially in online slang, “backroom” can easily imply:

- porn settings,

- secret sexual behavior,

- unethical political schemes,

- digital “dark room” practices.

This shift wasn’t academic — it was cultural, commercial, and generational.

🔹 Why It Matters: The Pragmatic Trap

Students today do not learn English from textbooks alone.

They learn from:

- TikTok,

- YouTube shorts,

- Discord chats,

- gaming slang,

- memes,

- AI-generated content with zero ethical filters.

That’s why a student might say:

“He’s such a backroom boy” —

and mean well,

but the listener may hear: pervert, creep, or conspirator.

This is not their fault.

But if we as teachers don’t explain it — they’ll be the ones who pay for our silence.

🔹 Between Language and Conscience

Some may ask:

“Why bother teaching this? It’s not on the exam.”

True. But real mistakes don’t always happen on exams.

They happen in real life — in job interviews, cross-cultural relationships, public speaking, casual banter.

And one wrong word, taken from the wrong context, can damage credibility in seconds.

That’s why I explain it.

Even if it makes the student uncomfortable.

Even if it’s not “appropriate for the level.”

Even if it’s not “on the list.”

Because my job is not to recite content.

My job is to help someone not make a fool of themselves in front of the wrong audience.

“Not every student likes what I say.

But I’d rather help them grow than keep them comfortable.”

🔹 The Teacher’s Dilemma: Say What Sells — or Say What Serves?

In schools with fixed methodology, you’re often forced to stick to the curriculum.

You can’t go off-script.

You can’t explain cultural nuance.

You can’t talk about how words really behave in today’s world.

But students don’t live in curriculums.

They live in messy, meme-filled, sexualized, ironic, coded reality.

As a teacher, I’ve had two options:

- Say only what’s expected — and keep the student happy.

- Say what’s needed — and risk discomfort or criticism.

I chose the second.

“We don’t tell you what you want to hear.

We tell you what helps you learn.”

And if I lost a student because of that honesty — so be it.

At least my conscience is clean.

🔹 Final Word: “So That I Don’t Burn for It Later”

A student once asked me if I teach all this street-level, double-coded, TikTok-corrupted vocabulary.

I said no.

“But if you ask — I’ll explain.

Not to entertain you.

But so that you don’t step into something stupid and say it in public.”

Because that would be on me.

And maybe — just maybe —

that’s one frying pan less waiting for me in hell.

© Tymur Levitin — Founder, Director & Senior Instructor

Start Language School by Tymur Levitin (Levitin Language School)

Global Learning. Personal Approach.