“Präteritum is not just ‘the written past.’ It is the tense of bare fact, narrative distance, and German identity.” — Tymur Levitin

Introduction: Beyond “Written Past”

Every learner hears:

- Präteritum = written German

- Perfekt = spoken German

That is not false, but it hides the real picture.

Präteritum is the tense of facts, narration, and formality. It is the tense that says: “This happened. Period.”

To understand it, we need to dig down to its history, its forms, and its survival in modern usage.

1. The Core Function: Bare Fact

- Ich spielte gestern Fußball. → I played. The fact itself.

- Es regnete den ganzen Tag. → It rained all day.

👉 No focus on result or consequence. Just the event, as a given fact.

2. Forms: Weak vs Strong Verbs

Weak verbs (regular)

- spielen → spielte, ich spielte, wir spielten.

Strong verbs (irregular, stem change)

- sehen → sah, ich sah, wir sahen.

- gehen → ging, ich ging, wir gingen.

Mixed verbs

- bringen → brachte.

- denken → dachte.

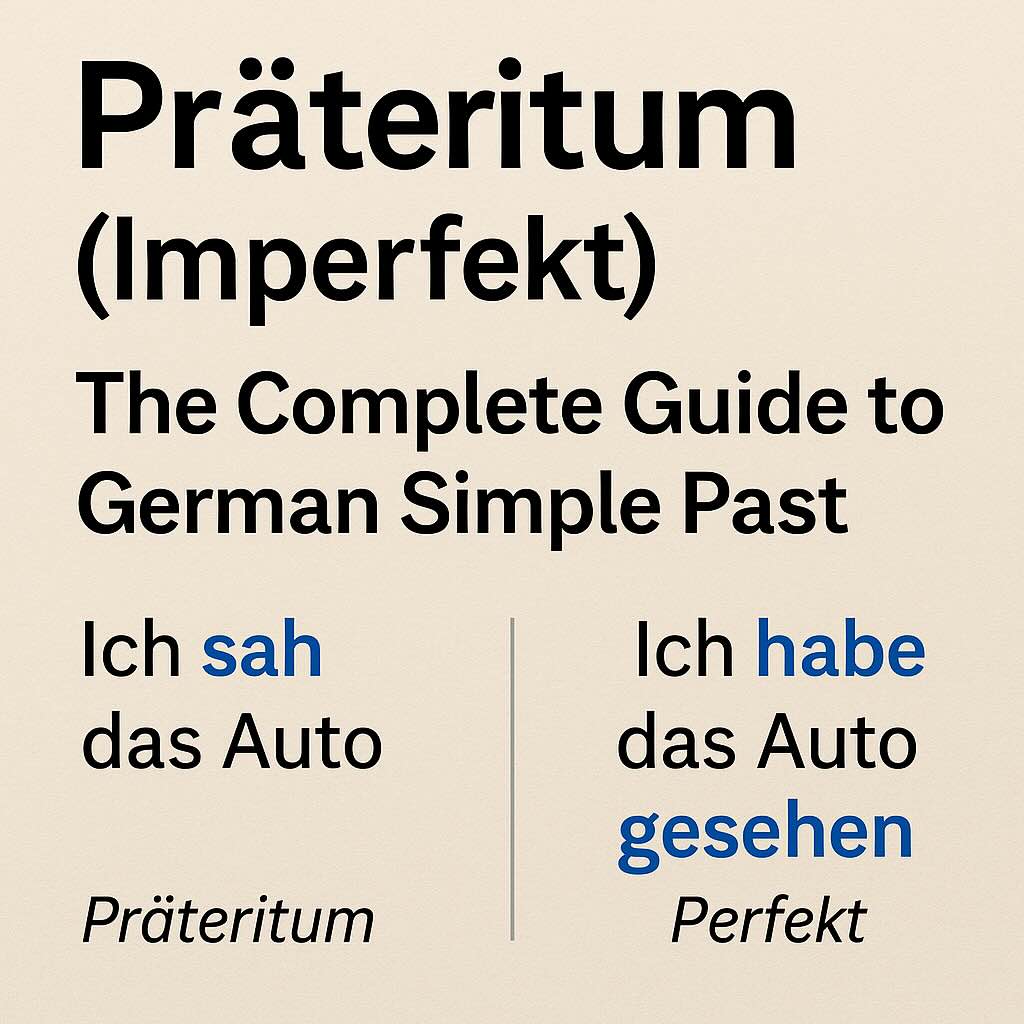

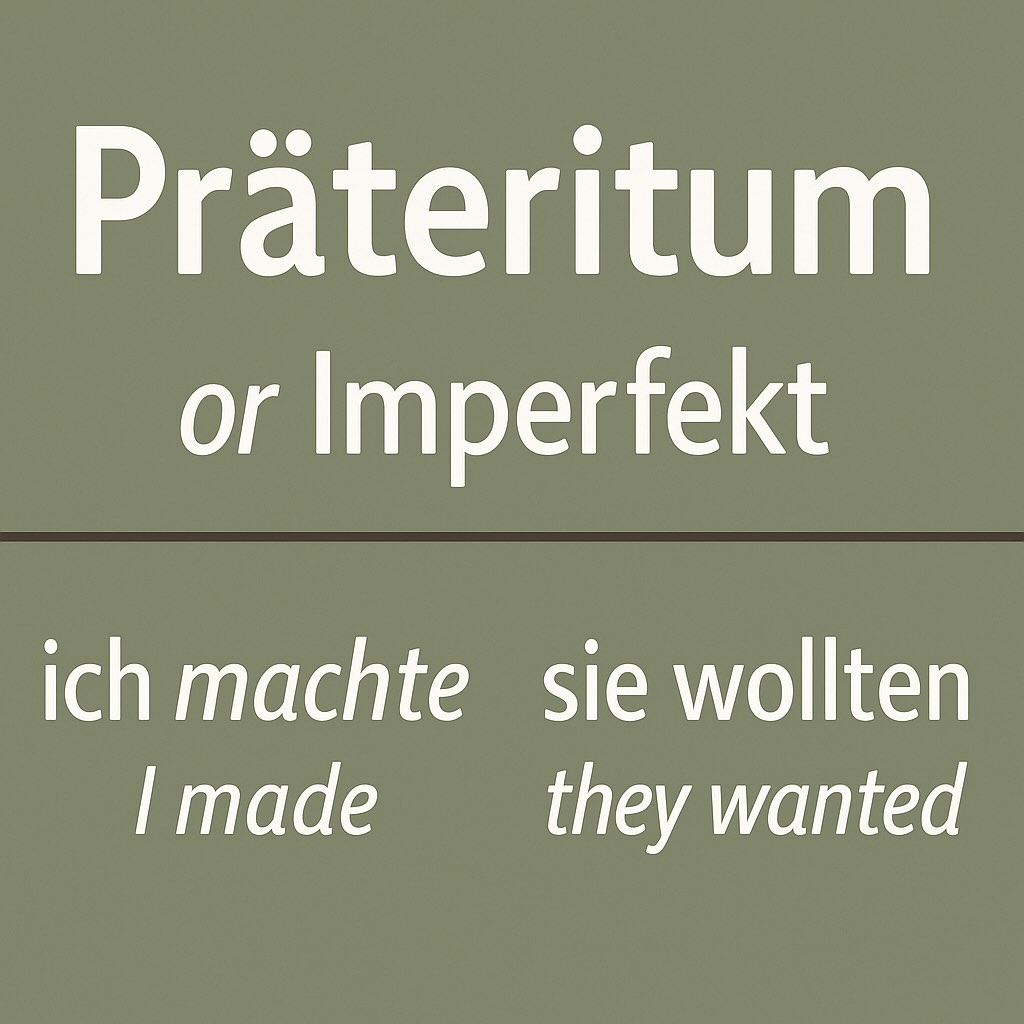

Präteritum vs Imperfekt — Two Names, One Tense

Learners often get confused: why do some textbooks say Präteritum, while others say Imperfekt? Are these two different tenses?

👉 The answer: No. They are two names for the same tense.

- Präteritum = the traditional German grammatical term.

- Imperfekt = the Latin-based term used in comparative linguistics (alongside Perfekt).

Historically, the Latin imperfectum meant an “unfinished” action, contrasting with perfectum (a “completed” action). When German grammars were standardized, this label was borrowed. But in modern German, Imperfekt and Präteritum refer to the exact same tense.

📍 Important difference:

- In Romance languages (Spanish imperfecto, French imparfait), “imperfect” still means an ongoing or habitual past action (ich spielte oft).

- In German, this nuance is not separate: Imperfekt = Präteritum.

That is why you will see both terms in books and exams. They are synonyms, not two different tenses.

Table: “Imperfekt” Across Languages

| Language | Term | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| German | Präteritum / Imperfekt | Same tense (simple past, bare fact) | ich spielte |

| Latin | imperfectum | “unfinished past” (contrast to perfectum = completed) | amabam (“I was loving”) |

| Spanish | imperfecto | ongoing/habitual past | jugaba (“I used to play”) |

| French | imparfait | ongoing/habitual past | je jouais (“I was playing”) |

| English | imperfect (rare, academic) | not used in daily grammar; refers to continuous past | — |

3. Historical Background

- In Middle High German, Präteritum was the main past tense, used both in speech and writing.

- Over centuries, Perfekt expanded into speech, especially in southern regions.

- Präteritum gradually retreated into writing and formal registers, surviving strongest in the north.

4. Modern Distribution

North Germany

- Still natural in speech: ich war, ich hatte, ich konnte.

South Germany / Austria / Switzerland

- Almost completely replaced by Perfekt in speech:

- Instead of ich war, people say ich bin gewesen.

- Instead of ich hatte, people say ich habe gehabt.

Writing and media

- Narratives (books, fairy tales, reports, news) → Präteritum dominates.

- Dialogue in novels → often Perfekt for realism.

5. Modal Verbs in Präteritum

- können → ich konnte.

- müssen → ich musste.

- dürfen → ich durfte.

- sollen → ich sollte.

- wollen → ich wollte.

👉 These forms are alive even in spoken south German.

No one says ich habe gekonnt in everyday talk; they use ich konnte.

6. Auxiliaries in Präteritum

- sein → ich war, wir waren.

- haben → ich hatte, wir hatten.

These are very frequent even in southern speech.

Perfekt (ich bin gewesen, ich habe gehabt) exists, but war/had still feel lighter in quick conversation.

7. Narrative Distance and Style

Präteritum creates a sense of distance:

- Er stand auf und ging hinaus. (narrative style).

- Used in reports, chronicles, novels, fairy tales:

- Es war einmal…

Perfekt would sound too personal or oral here.

8. Edge Cases and Paradoxes

1. Replacement that doesn’t work

- Ich war gewesen ≠ ich war. (war gewesen = Plusquamperfekt).

- Ich hatte gehabt = correct but heavy.

2. Modal verbs prefer Präteritum in speech

- South German speech:

- ich konnte, ich musste, ich wollte (Präteritum).

- Rarely ich habe gekonnt outside exams.

3. Northern habit

- ich sagte, ich dachte in everyday talk.

- In the south, same context → Perfekt: ich habe gesagt, ich habe gedacht.

9. Tables for Survival

Weak, strong, mixed

| Verb | Perfekt | Präteritum | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| spielen | ich habe gespielt | ich spielte | weak |

| sehen | ich habe gesehen | ich sah | strong |

| gehen | ich bin gegangen | ich ging | strong |

| bringen | ich habe gebracht | ich brachte | mixed |

| denken | ich habe gedacht | ich dachte | mixed |

Auxiliaries

| Verb | Perfekt | Präteritum | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| sein | ich bin gewesen | ich war | Perfekt rare in south |

| haben | ich habe gehabt | ich hatte | Perfekt rare in south |

Modals

| Verb | Perfekt | Präteritum | Real usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| können | ich habe gekonnt | ich konnte | Präteritum in speech |

| müssen | ich habe gemusst | ich musste | same |

| dürfen | ich habe gedurft | ich durfte | same |

| sollen | ich habe gesollt | ich sollte | same |

| wollen | ich habe gewollt | ich wollte | same |

10. Exam vs Real Life

Exams / Standard

- Write Perfekt for spoken dialogues.

- Use Präteritum for narratives, reports, news.

- Conjugation: memorize weak/strong/mixed paradigms.

Real life

- North: Präteritum natural in speech.

- South: Perfekt dominates, except modal verbs, sein, haben.

- Writing: Präteritum dominates, even for southern authors.

11. Philosophical Note

Perfekt describes state/result.

Präteritum describes bare fact, stripped of result.

- Ich war dort. = I was there (fact).

- Ich bin dort gewesen. = I was there, and this fact matters now.

👉 The difference is not about grammar only. It is about how Germans choose to see events: as facts or as results.

Conclusion

Präteritum is not dead.

It lives in the north, in modal verbs, in writing, and in the German sense of narrative distance.

Perfekt tells us what is relevant now.

Präteritum tells us simply: it happened.

TL;DR

- Präteritum = fact. Perfekt = result.

- Weak verbs: spielte, lernte. Strong verbs: sah, ging. Mixed: brachte, dachte.

- North: Präteritum still spoken. South: Perfekt dominates, except modals + sein/haben.

- Modals: almost always Präteritum in speech.

- Writing: Präteritum everywhere (fairy tales, reports, novels).

Recommended Articles

About the Author

Tymur Levitin — Founder, Head Teacher & Translator

© Tymur Levitin — Levitin Language School / Start Language School by Tymur Levitin

Global Learning. Personal Approach.